Table of contents

Today, Print on Demand (POD) is so integrated into eCommerce that customers often don’t realize the product they ordered was created specifically for them. Yet just a few decades ago, manufacturing one unit at a time seemed counterintuitive.

Traditional printing required large-scale production to be profitable, forcing businesses to risk stocking inventory that might never sell. POD flipped that logic – why gamble on demand when you could produce after purchase?

This is the history of Print on Demand: where it started, how it became a global industry, and what technologies and cultural shifts made it possible. We’ll explore the chemistry of inks, the rise of digital printing, key industry milestones, and the sustainability challenges it faces.

You’ll see how POD went from a niche publishing experiment to a defining force in modern eCommerce, reshaping how creators and brands bring ideas to market.

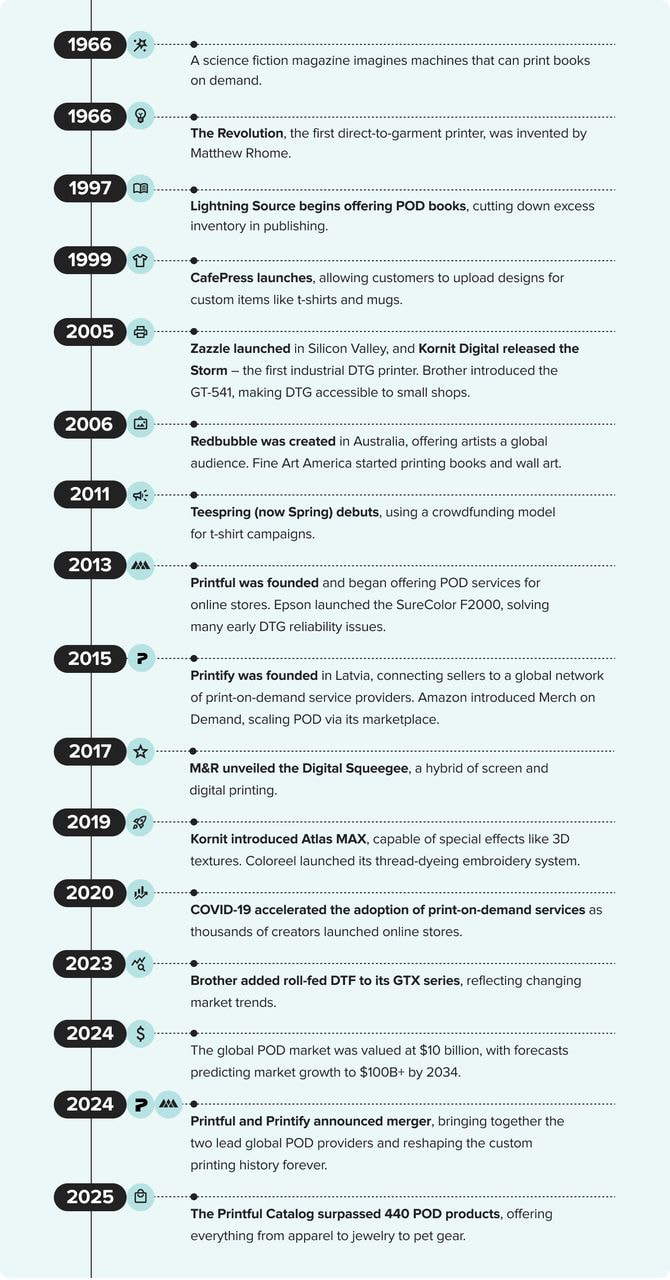

The evolution of Print on Demand

Origins: Where POD began

Publishing roots

Before t-shirts and mugs, Print on Demand began with books. By the mid-20th century, futurists such as Frederik Pohl were already speculating about vending-machine-style book printers – a vision later realized in prototypes like the MTI PerfectBook and the Espresso Book Machine.

Xerox’s Espresso Book Machine. Salon du Livre de Paris, 2015. CC BY-SA 2.0.

In the late 1990s, publishers faced a growing problem: unsold titles filling warehouses. Traditional publishing depended on bulk offset printing, a model that came with significant risks if a book flopped.

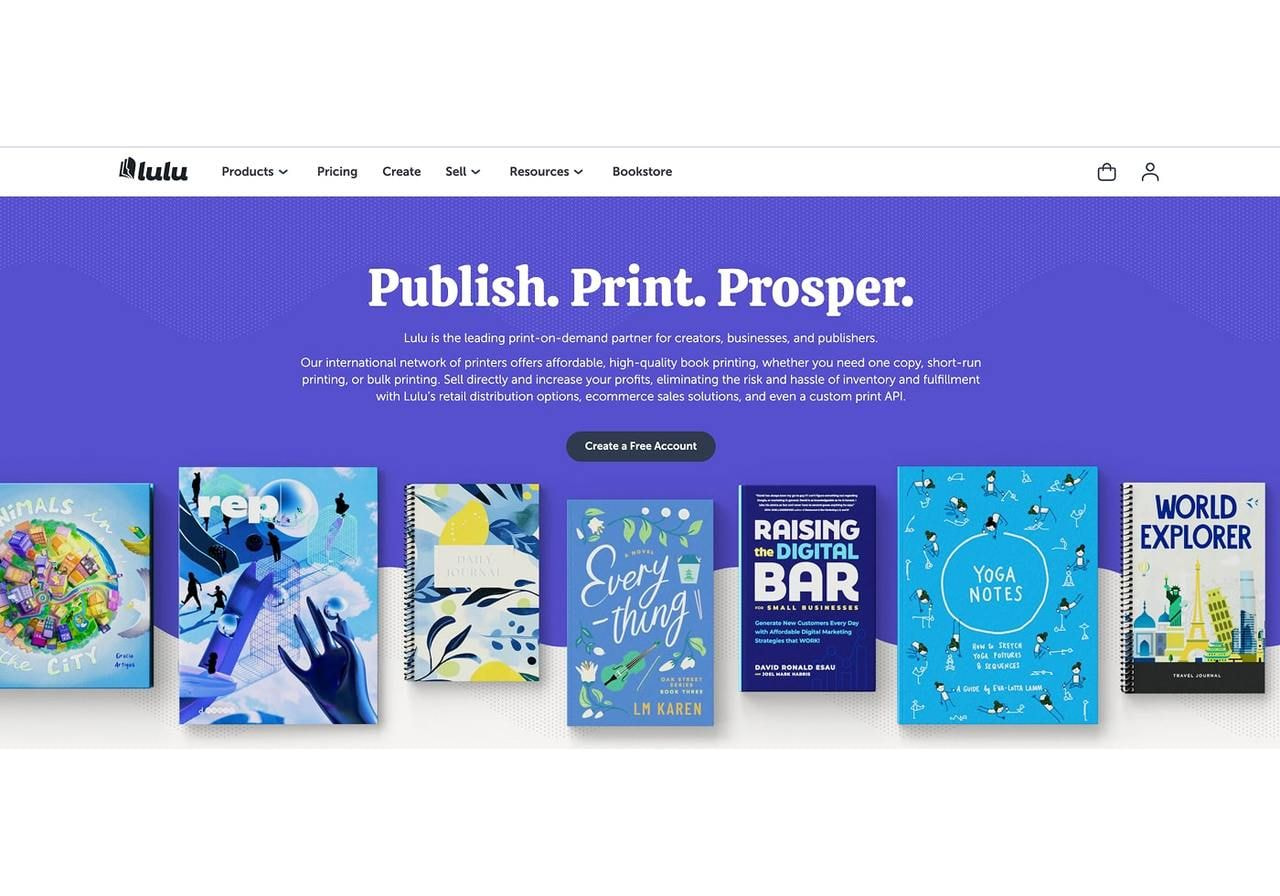

The solution was simple yet radical – print books only after an order was placed. Companies like Lightning Source (1997) and Lulu (2002) pioneered this shift, offering authors a way to publish without minimum orders or large upfront costs.

A writer could upload a manuscript, and a single copy would be digitally printed and shipped. Academic publishers quickly saw the advantages, using POD to manage low-demand titles more cost-effectively, reduce financial risk, and adapt their business model to a changing environment.

Lulu press

Merchandise breakthrough

Almost simultaneously, entrepreneurs asked, “If you can print a book on demand, why not a shirt?”

In 1999, CafePress launched what many call the “grandfather” of POD merchandise, allowing anyone to upload a design for t-shirts, mugs, or posters. For the first time, artists could sell physical products without keeping stock. The 2000s saw similar platforms emerge globally.

-

Spreadshirt (2002) in Germany lets users create custom shirts with text and graphics, using heat-transfer vinyl for one-offs.

-

Zazzle (2005) in Silicon Valley combined a marketplace with product customization tools.

-

Redbubble (2006) in Australia gave independent artists a platform to sell their work on a global scale.

These companies marked a turning point, creating a home for niche markets – fandoms, political movements, or inside jokes – that could never support a traditional retail run.

Why these early platforms mattered

The leap from books to merchandise transformed POD into something more than a publishing experiment. By offering custom items with no initial investment, these platforms made manufacturing and selling custom items more accessible.

An artist could sell a print of their work on a coffee mug without ever touching the product. A college student could design shirts for a campus event without ordering hundreds of extras.

More importantly, they flipped the traditional supply chain from produce then sell to sell then produce. This logic would eventually ripple through the broader industry, setting the stage for massive growth.

By the mid-2000s, POD was no longer a clever fix – it was a new way of thinking about commerce.

The technologies that made it possible

The success of Print on Demand has always depended on technology. Without the right printing methods, inks, and machines, producing one-off items would have been far too expensive and inefficient.

From the dominance of screen printing in the 20th century to today’s high-speed systems, the digital textile printing evolution opened new possibilities for what could be made on demand.

Printing methods over time

1. Screen printing

The origins of modern print-on-demand fulfillment can’t be separated from screen printing. The method first appeared in China during the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE), later spreading to Japan before reaching the West.

In its modern form, screen printing took off in the early 20th century, but its big moment came in the 1960s thanks to two key breakthroughs happening at once.

-

On the cultural front, artist Andy Warhol made it famous with his iconic pop art.

-

On the manufacturing front, Michael Vasilantone’s invention of the multi-color rotary press made it fast and affordable to print those kinds of bold designs on t-shirts for the masses.

Marilyn Monroe by Andy Warhol (1967). Source: The Museum of Modern Art

Screen printing excels at durability and cost-efficiency in bulk, but its complex, multi-screen setup posed challenges for one-off POD orders. Each color in a design requires a separate screen, and setup takes time and resources.

While still used in hybrid setups, digital solutions have largely taken over for single-item printing.

2. Heat transfers and vinyl

Before digital methods advanced, heat transfers and vinyl were the go-to for smaller runs. Designs could be printed on special paper with an inkjet or laser printer, then heat-pressed onto a shirt.

Vinyl cutters allowed letters and shapes to be applied as custom items, such as team jerseys with individual names. Companies like Spreadshirt leaned heavily on these techniques in the early 2000s, making personalization accessible but still limited in complexity.

3. Direct-to-garment (DTG)

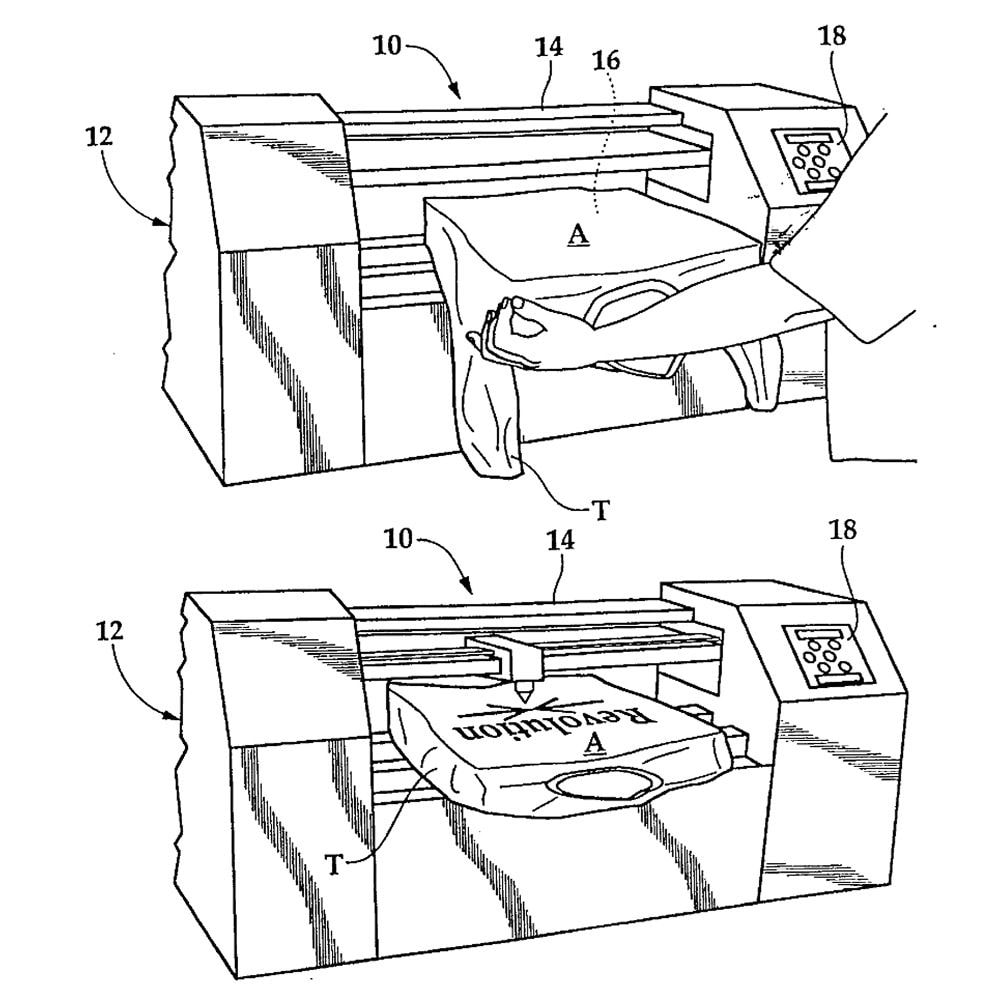

A game-changer arrived in 1996 – the first commercial DTG printer. Invented by Matthew Rhome, it proved that a digital inkjet system could print directly on fabric.

Mathew Rhome’s “Revolution,” the first DTG printer. Source: US Patent US6095628A

However, the real breakthrough came in the mid-2000s, when companies like Kornit, Brother, and Mimaki launched commercial DTG printers.

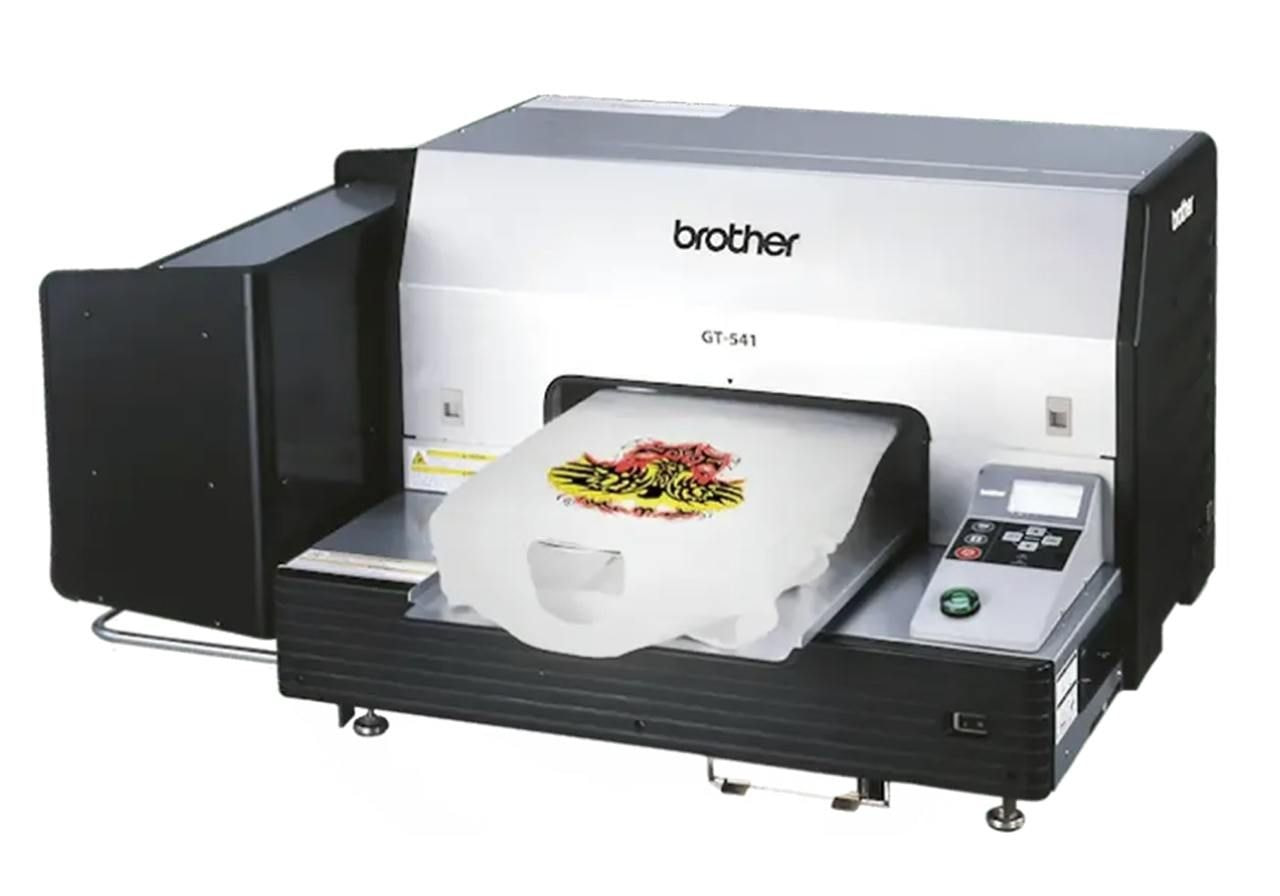

Brother’s GT-541 (2005) was a milestone – a relatively reliable, computer-to-shirt system that could handle full-color designs.

The Brother GT-541 (2005). Source: Brother

Around the same time, DuPont introduced titanium dioxide-based white ink, which solved the long-standing limitation of printing on dark garments. This innovation – quickly adopted by Kornit – opened DTG up to a much wider range of apparel.

DTG made true on-demand production viable and is now the workhorse of POD for cotton-based apparel.

Explore more

Check out our DTG vs screen printing comparison.

4. Sublimation

Sublimation printer. Source: Adobe

Dye-sublimation printing was first developed in the 1950s by Noël de Plasse at the French company Lainière de Roubaix. Using heat to bond dye into polymer-coated surfaces, the technique made it possible to produce vibrant all-over prints and edge-to-edge designs.

Decades later, it became very important to POD because it works perfectly on polyester fabrics and polymer-coated goods like mugs. By using heat to bond dye into the surface itself, sublimation delivers vivid, durable, all-over prints.

Sublimation turned drinkware, phone cases, blankets, pillows, and sportswear like leggings, into POD staples in the 2000s and 2010s.

5. Direct-to-film (DTF)

The 2020s introduced another breakthrough – direct-to-film (DTF) printing. Instead of printing directly on fabric, the design is printed onto a special film, coated with adhesive powder, and heat-pressed onto the garment. The advantage is versatility, as DTF works on cotton, polyester, blends, and even tricky surfaces like nylon.

For POD, this opened new market trends, enabling sellers to offer items that DTG struggled with. Many fulfillment centers now run DTG and DTF side by side, routing orders to whichever printing method is best for the material.

6. Embroidery, engraving, and UV printing

Not all print-on-demand methods rely on ink. Previously available only for luxury goods, custom embroidery became widely available in the 2010s as fulfillment centers invested in fleets of computerized machines, making it possible to create one-off custom caps, polos, and jackets.

Laser engraving expanded customization into jewelry, tumblers, and wooden goods.

UV printing allows direct printing on rigid items like phone cases or acrylic plaques. Niche companies like Shapeways have even incorporated 3D printing, proving that Print on Demand can extend far beyond textiles.

Hardware innovations at a glance

The introduction of more advanced hardware made Print on Demand scalable. By the 2020s, new DTG and DTF printers could output hundreds of prints per hour, rivaling traditional methods in efficiency. Some models include robotics to load and unload garments, or cloud connectivity to integrate with eCommerce platforms.

-

Revolution (1996) – The first DTG prototype.

-

Kornit Storm (2005) – Integrated pretreat + CMYK + white, industrial-grade.

-

Brother GT-541 (2005) – Reliable entry into DTG.

-

Epson F2000 (2013) – Solved maintenance issues and boosted adoption.

Inks: The chemistry of change

Hardware and technology aren’t the only parts of printing that have evolved over the years. Ink, another key ingredient of a beautifully made print-on-demand product, has also undergone a few changes.

1. Plastisol dominance

In the mid-20th century, plastisol inks transformed screen printing. They were thick, vibrant, and didn’t dry on the screen, enabling efficient production and easier cleanup.

For decades, plastisol defined the look of printed t-shirts – bold, raised designs with durability. But plastisol contained PVC and phthalates, raising concerns about health and sustainability.

2. Water-based resurgence

By the 2000s, regulatory shifts and consumer demand pushed the industry back toward water-based inks.

These provided a softer feel, breathable prints, and a better environmental profile. Today, many POD providers embrace water-based inks to align with the values of minimizing waste and reducing the environmental impact of production.

3. DTG ink breakthroughs

Early DTG printers struggled because they couldn’t print on dark fabrics. The introduction of white ink in 2005 by DuPont changed that, making full-color prints possible on almost any garment.

Over time, DTG inks evolved into eco-certified, water-based pigment formulations that adhere to multiple fabrics and last through washes. Modern inks combine vibrancy, safety, and efficiency – a stark contrast to the traditional printing methods of the past.

Why technology mattered

The technological arc, from plastisol inks to eco-pigments, from screen presses to automated DTG systems, and broader advancements in garment printing, transformed Print on Demand from a small studio operation into an industrial powerhouse. Each advance reduced barriers – less initial investment, faster turnaround, broader material compatibility.

Technology didn’t just improve print quality – it redefined the economics of the POD industry. By combining automation, digital flexibility, and a distributed network of providers, Print on Demand became not only feasible but scalable, ready to serve millions of orders in an ever-changing world of fashion, retail, and personalization.

From t-shirts to… everything

For many people, when thinking of Print on Demand, the first image that comes to mind is usually a cotton t-shirt. And it makes sense – t-shirts were the earliest and most popular canvas for custom designs, easy to ship, and perfect for personal expression. However, the story of POD is also the story of steady expansion into almost every product category imaginable.

Staple beginnings

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, POD catalogs were slim. Platforms like CafePress and Spreadshirt focused on a handful of core items: t-shirts, mugs, posters, and stickers. These staples were simple to produce using DTG, heat transfers, or sublimation.

They also matched the needs of early niche markets, like fan clubs, political movements, or student groups that wanted a quick run of custom clothing and other items without large minimum orders.

Despite the limited range, these early products proved a powerful idea: people valued the ability to buy something that didn’t exist until they clicked “order.”

Expansion into lifestyle and niches

As technology advanced in the mid-2000s, print-on-demand catalogs diversified. Sublimation and large-format inkjets made it possible to print on textiles beyond tees – tote bags, mousepads, aprons, and calendars entered the mix. Wall art became a major category, too, as platforms like Redbubble and Society6 gave independent artists the chance to sell posters and canvases without managing inventory.

Custom tote bag. Source: Printful Catalog

The arrival of smartphones created an entirely new category. Around 2010, custom phone cases surged in popularity, usually printed via sublimation or UV flatbed printers. The shift reflected a broader trend – POD wasn’t only about apparel, but about helping people personalize their daily lives.

Fashion, home goods, and personalization

By the 2010s, POD embraced full-bleed sublimation (also called all-over-print or AOP) for polyester apparel. Leggings, yoga pants, and bomber jackets with all-over patterns became high-demand products. Sellers also introduced custom products for the home – pillows, blankets, curtains, even shower curtains – often decorated with customer photos or artwork.

Personalization surged in popularity during this era. Consumers increasingly wanted items tailored to them – not only artist-made designs, but products with a photo, a name, or a favorite color. What had once been limited to vinyl lettering in the early 2000s expanded into a much wider range of options.

The 2020s and hyper-niche products

The last decade saw POD stretch into areas that once seemed improbable. Pet lovers can now order custom bandanas, bowls, and beds. Jewelry can be engraved or UV-printed with personal messages. Some print-on-demand platforms even print fabric panels that are later assembled into sneakers.

For online stores, this explosion of variety is a competitive advantage. Sellers can test creative ideas quickly, adding new items to meet emerging markets or seasonal consumer preferences. Because there are no warehouses full of stock to clear, the risk of experimentation is low.

The sheer range of POD products today reflects how the business model has adapted to a global audience with highly diverse tastes, covering various products across fashion, home, and lifestyle.

Whether it’s a blanket for a gamer’s bedroom, a phone case featuring a viral meme, or a commemorative t-shirt for a local sports team, POD provides a way to fulfill the demand immediately and economically.

Why product expansion mattered

The shift from a handful of basics to hundreds of items opened up the business model for every type of seller.

Now, print-on-demand products include everything from jewelry to furniture, giving entrepreneurs an almost limitless toolkit. This growth has also pulled in bigger brands, who see POD as a way to test designs, reach potential customers, and avoid the pitfalls of excess inventory.

For many, the takeaway is simple: POD offers endless possibilities. The model adapts to consumer demand, whether that means nostalgic posters, personalized gifts, or experimental fashion. Each expansion has brought POD closer to being not just a clever workaround for small creators but a core pillar of modern retail.

POD and the creator economy

Print on Demand expanded beyond new product categories and changed who could participate in commerce. What once required warehouses, logistics contracts, and major retail partnerships became accessible to anyone with a design file and an internet connection.

This shift powered the rise of the creator economy.

Empowering independent creators

For artists and illustrators, POD services like Redbubble and Society6 provided a direct line to buyers. An independent creator could upload artwork, set a price, and have it printed on posters, mugs, or t-shirts. No stocking shelves, no shipping boxes.

This arrangement gave artists an outlet for creative ideas that might never attract traditional publishers or manufacturers.

The same was true for indie bands and political movements. Merchandise had long been a way to rally support, but POD eliminated the gamble of overordering. A musician could sell shirts with tour artwork, confident they’d never be left with unsold boxes. Activist groups could launch campaigns overnight, tailoring products to specific events or causes.

Influencers and microbrands

The 2010s added social media to the mix. As Instagram, YouTube, and later TikTok exploded, creators with loyal followings looked for ways to monetize their communities. POD became a natural fit.

By linking an online store to platforms like Shopify or Etsy, influencers could launch product lines without warehouses or sewing machines.

These microbrands often leaned on highly personal offerings, like a podcaster’s inside joke on a mug or a TikToker’s catchphrase on a hoodie.

For fans, buying was less about the object than about connecting with the creator. For creators, POD offered artistic freedom and branding control with little initial investment.

Culture and commerce intertwined

The creator economy turned cultural moments into commerce almost instantly. A viral meme could become a t-shirt within hours. A YouTube tutorial artist could branch into selling custom products. Small collectives of designers could test styles, gather feedback, and pivot quickly, thanks to POD’s lack of upfront costs.

This flexibility matched the fast-changing pace of online culture. When a phrase or image caught fire, sellers could transform it into merchandise almost overnight. POD absorbed the production risk, letting creators focus on engagement and storytelling – often the first step for those starting a small clothing business from home.

Why the creator economy mattered for POD

By empowering independent creators, Print on Demand became the go-to method for creating merchandise for niche fandoms, viral content, and grassroots movements.

At the same time, it attracted established brands. Fashion labels and entertainment companies began testing designs through POD before committing to huge volume orders, using the model to gauge interest from potential customers. In this way, creator-driven retail influenced larger players, showing that commerce could thrive outside the old rules.

Print-on-demand statistics: Growth and challenges

The story of POD is also the story of an industry maturing. What began as scattered experiments in publishing and merchandise is now a global network of fulfillment providers, platforms, and creators. Along the way, the POD industry has experienced rapid market growth, intense competition, and persistent challenges.

Print-on-demand industry growth

Estimates placed the global print-on-demand market size at more than USD 10.2 billion in 2024, with forecasts suggesting it could approach $100 billion by 2034. This implies a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of around 25–26%.

Other industry analyses are more conservative: Grand View Research projects the market will reach about $57.5 billion by 2033, while Future Market Insights forecasts nearly $90 billion by 2035, both citing CAGRs around 23%.

Several factors explain this surge. The spread of reliable digital printing technology lowered production barriers. Integrations with eCommerce platforms like Shopify and Etsy gave sellers plug-and-play storefronts. Social media and influencer marketing expanded the pool of potential customers, while fulfillment networks scaled up to serve a global audience.

Print on Demand has become a solid part of buying and selling merchandise today. People now see it as part of the bigger picture in eCommerce, right alongside things like subscription boxes, dropshipping, and influencer brands.

Players and competition

A handful of companies define the POD industry. Fulfillment providers like Printful, Printify, Gooten, and Gelato serve merchants who run their own online stores. Their focus is on product quality, shipping reach, and integrations with demand platforms.

Marketplaces take a different approach. Redbubble, Society6, Spring, and Amazon’s Merch on Demand let artists upload designs and sell directly through the platform. Sellers benefit from built-in traffic but trade off control and margins.

The diversity of providers shows how far the POD industry has come. In the early 2000s, only a few print-on-demand companies experimented with one-off merchandise. Now, several companies compete across regions, each with unique strengths in product range, geography, or price. Established brands also lean on POD to test collections or launch limited runs, adding to the competition.

Challenges and barriers

While POD has experienced fantastic growth, there are still some hurdles to overcome.

-

Profit margins: Producing one item at a time is usually more expensive than bulk manufacturing. Sellers must balance higher base costs with pricing that remains attractive to potential customers.

-

Quality control: Differences in printing methods – whether DTG, DTF, or sublimation – can impact the customer experience. Large providers invest heavily in consistency, but smaller operators sometimes struggle.

-

Copyright and IP disputes: The open nature of print-on-demand services has led to repeated copyright infringement controversies. Marketplaces often battle takedown requests for unlicensed fan art or counterfeit designs.

-

Scaling fulfillment: Meeting surges in demand during holidays tests even the largest networks. Automating shipping processes and optimizing production queues are ongoing challenges.

-

Consumer perception: Some buyers still associate POD with novelty shops or low-end goods, even as quality has improved dramatically. Overcoming this perception requires continued investment in materials, printing technology, and brand partnerships.

Why the business story matters

POD’s history of growth mirrors the pressures and opportunities of modern retail. On one hand, it offers freedom, flexibility, and reduced excess inventory. On the other hand, it must continually improve efficiency, cost, and reputation.

As the industry grows, so does its complexity. Sellers have more tools and on-demand services than ever, but they also face a more crowded market. For providers, the challenge is to maintain reliability while innovating for ever-changing consumer preferences and print-on-demand trends.

Despite the challenges, Print on Demand remains one of the most dynamic business models of global commerce. Its steady expansion shows that the model is not a passing trend but a durable framework reshaping how products are designed, sold, and delivered.

Sustainability: Promise and reality

One of the strongest arguments in favor of Print on Demand is its potential to reduce waste. Traditional manufacturing models usually only print large-volume orders, often resulting in shelves filled with unsold goods or warehouses stacked with stock that may never find buyers.

What POD solves

By producing only after a purchase is made, POD eliminates much of that risk. For a seller, there are no minimum orders to meet, and no unsold boxes are tucked away in storage. For the environment, this translates into fewer products destined for landfills. In this way, POD represents a meaningful step toward minimizing waste in fashion and consumer goods.

Global fulfillment networks add another layer of efficiency. Instead of shipping bulk orders across oceans, POD providers like Printful can route production to the facility closest to the customer. Shorter shipping processes mean reduced transport emissions and faster delivery.

Environmental trade-offs

Print on Demand isn’t entirely impact-free. Each printing method has its own footprint. DTG relies on water-intensive pretreatment and creates wastewater streams. DTF, while versatile, uses PET transfer films that must be discarded after use. Sublimation inks require polyester fabrics or polymer-coated items, which complicates recycling. Even screen printing, the most established process, depends heavily on chemicals for cleaning and setup.

This mix creates a complicated picture. Print on Demand avoids overproduction but still generates waste through consumables and byproducts.

Eco innovations

Providers and equipment manufacturers have responded with steady improvements. Kornit introduced waterless DTG systems that drastically reduce wastewater. Ink suppliers have developed water-based pigments that are certified by environmental standards. Some print-on-demand services now prioritize organic cotton and recycled polyester garments.

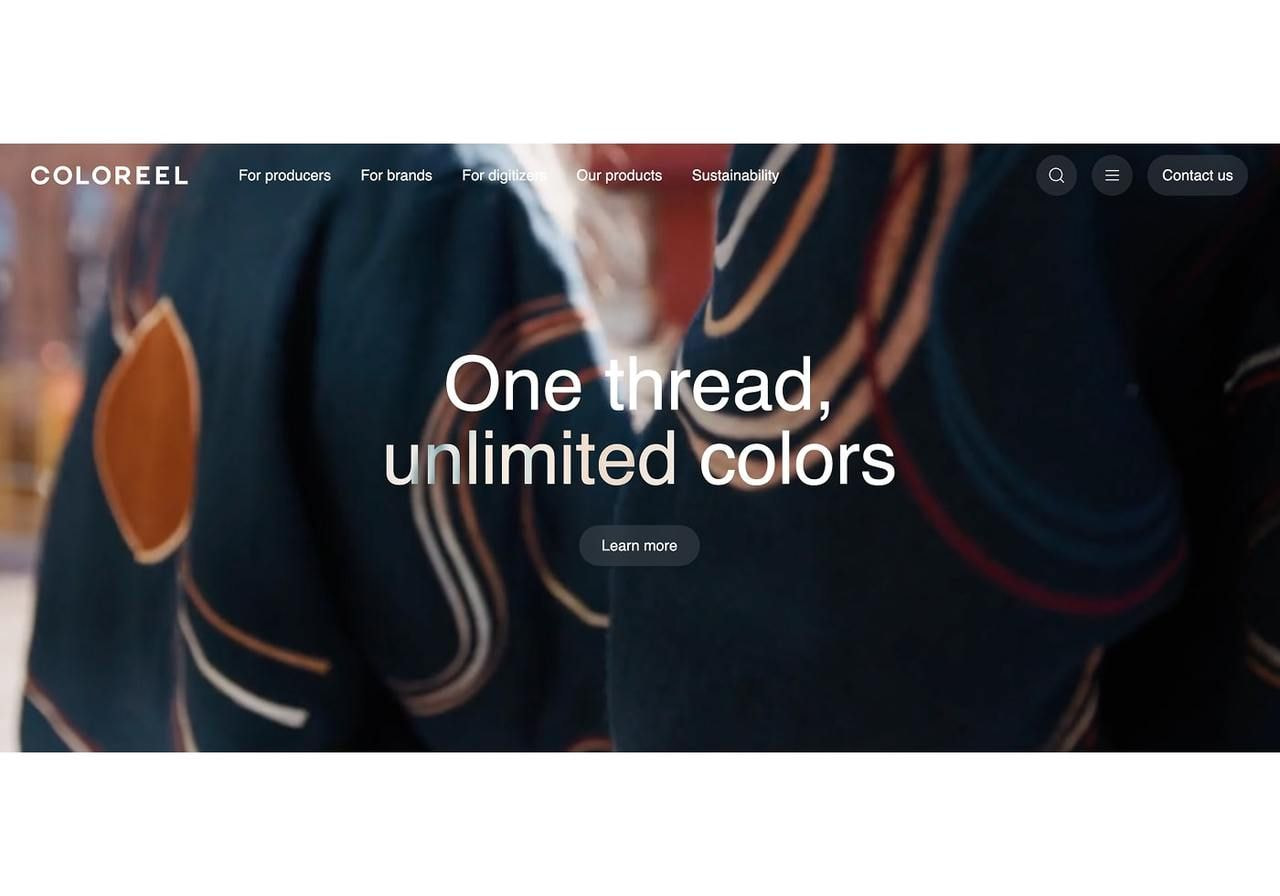

Embroidery has also made some strides toward eco-friendliness. Coloreel’s technology dyes thread during the embroidery process, eliminating the need for pre-dyed spools and reducing leftover materials. These steps may seem small, but they add up when you consider the high volumes of products coming out of the POD industry.

Coloreel

Balancing promise and reality

The environmental case for Print on Demand rests on comparison. When measured against traditional bulk production, POD often comes out ahead because it avoids overproduction and reduces warehousing.

But it’s still important to recognize that the environmental impact is not zero. Ever-changing sustainability requires constant improvement in inks, fabrics, and waste management.

The main takeaway for entrepreneurs and brands is that POD provides a way to align with consumer preferences for more responsible shopping. Customers increasingly expect transparency, so sellers who highlight eco-friendly products, ethical sourcing, and innovative printing technology make themselves much more attractive in a crowded marketplace.

The future of Print on Demand

The history of custom printing is still being written. The next decade will bring smarter factories, more adaptive printing technology, deeper personalization, and sustainability as a baseline.

Short-term outlook (1–3 years)

Microfactories and faster delivery. Fulfillment centers are moving toward smaller, automated units near major cities. Equipped with DTG, DTF, and sublimation, they can produce and ship a t-shirt locally within hours. Smarter routing software will balance speed, cost, and machine availability, pushing delivery windows down to a single day.

AI in design. Artificial intelligence is shifting from a standalone tool to an integrated part of POD platforms. Merchants will see automated mockups, pattern generation, and product suggestions, all formatted for the right printing method.

Hybrid machines. New print-on-demand hardware/equipment like Brother’s GTX series, which can toggle between DTG and roll-fed DTF, shows how manufacturers are collapsing processes into single units. This versatility lowers barriers to testing new products without major new investments.

Long-term outlook (3–10 years)

AR filters for beauty products. Source: Adobe

Beyond apparel. Non-clothing categories – furniture with custom fabrics, ceramics made with 3D printers, or personalized tech accessories – are set to grow faster than t-shirts and hoodies.

Immersive personalization. Shoppers will expect AR previews and generative design tools that tailor products to their individual style, making every purchase feel unique.

Large-scale automation. Robotic systems for garment loading, curing, and packaging could bring true lights-out factories to the POD industry, where entire orders are produced without human intervention.

Sustainability by default. Closed-loop recycling, organic textiles, and eco-certified inks will shift from optional selling points to mandatory standards as regulations and consumer demand grow.

Stronger oversight. Copyright protection and supply chain transparency will become central issues, with tighter rules on robotics that could also legitimize the industry further.

Looking ahead

In the coming decade, POD will likely evolve from a growth niche in eCommerce to a backbone of personalized manufacturing. For entrepreneurs and global brands alike, it represents not just a fulfillment option but a foundation for how products are created, tested, and delivered.

A print-on-demand timeline

1966 – A science fiction magazine imagines machines that can print books on demand.

1996 – The Revolution, the first direct-to-garment printer, was invented by Matthew Rhome.

1997 – Lightning Source begins offering POD books, cutting down excess inventory in publishing.

1999 – CafePress launches, allowing customers to upload designs for custom items like t-shirts and mugs.

2002 – Lulu.com was founded by Bob Young, and self-publishing POD became mainstream. Spreadshirt opened up in Germany, focusing on vinyl transfers and t-shirts.

2005 – Zazzle launched in Silicon Valley, and Kornit Digital released the Storm – the first industrial DTG printer. Brother introduced the GT-541, making DTG accessible to small shops.

2006 – Redbubble was created in Australia, offering artists a global audience. Fine Art America started printing books and wall art.

2011 – Teespring (now Spring) debuts, using a crowdfunding model for t-shirt campaigns.

2013 – Printful was founded and began offering POD services for online stores. Epson launched the SureColor F2000, solving many early DTG reliability issues.

2015 – Printify was founded in Latvia, connecting sellers to a global network of print-on-demand service providers. Amazon introduced Merch on Demand, scaling POD via its marketplace.

2017 – M&R unveiled the Digital Squeegee, a hybrid of screen and digital printing.

2019 – Kornit introduced Atlas MAX, capable of special effects like 3D textures. Coloreel launched its thread-dyeing embroidery system.

2020 – COVID-19 accelerated the adoption of print-on-demand services as thousands of creators launched online stores.

2023 – Brother added roll-fed DTF to its GTX series, reflecting changing market trends.

2024 – The global POD market was valued at $10 billion, with forecasts predicting market growth to $100B+ by 2034.

2024 – Printful and Printify announced merger, bringing together the two lead global POD providers and reshaping the custom printing history forever.

2025 – The Printful Catalog surpassed 440 POD products, offering everything from apparel to jewelry to pet gear.

Future outlook

-

AI-driven design tools integrated into print-on-demand platforms.

-

Microfactories delivering same-day on-demand production.

-

Robotics enabling near-fully automated POD fulfillment.

-

More extensive personalization reflecting changing consumer preferences.

-

POD as a default business model in global commerce.

Conclusion – The POD revolution continues

Print on Demand has evolved from a niche concept into a major eCommerce model. Producing items only when ordered reduces waste and makes customized products available worldwide. Today, it powers small businesses, independent creators, and global brands alike.

This growth has been fueled by advances in printing technology – DTG, sublimation, and DTF – combined with cultural shifts and entrepreneurial drive. Platforms like Printful made selling custom products globally both accessible and scalable.

Looking ahead, AI-driven design, robotics, and local microfactories will continue to transform POD. At the same time, sustainability will shift from being a competitive advantage to a baseline expectation, with eco-friendly blanks and near-zero waste becoming standard.

In essence, POD represents the shift from mass production to mass personalization, reshaping the future of eCommerce and the way people create, sell, and buy printed products.

Published author, scholar, and musician, Andris draws on over 11 years of experience in and outside academia to make complex topics accessible – from SEO and website building to AI and monetizing art. Devoted to his family and self-confessed introvert, he loves creating things, playing musical instruments, and walking around forests.